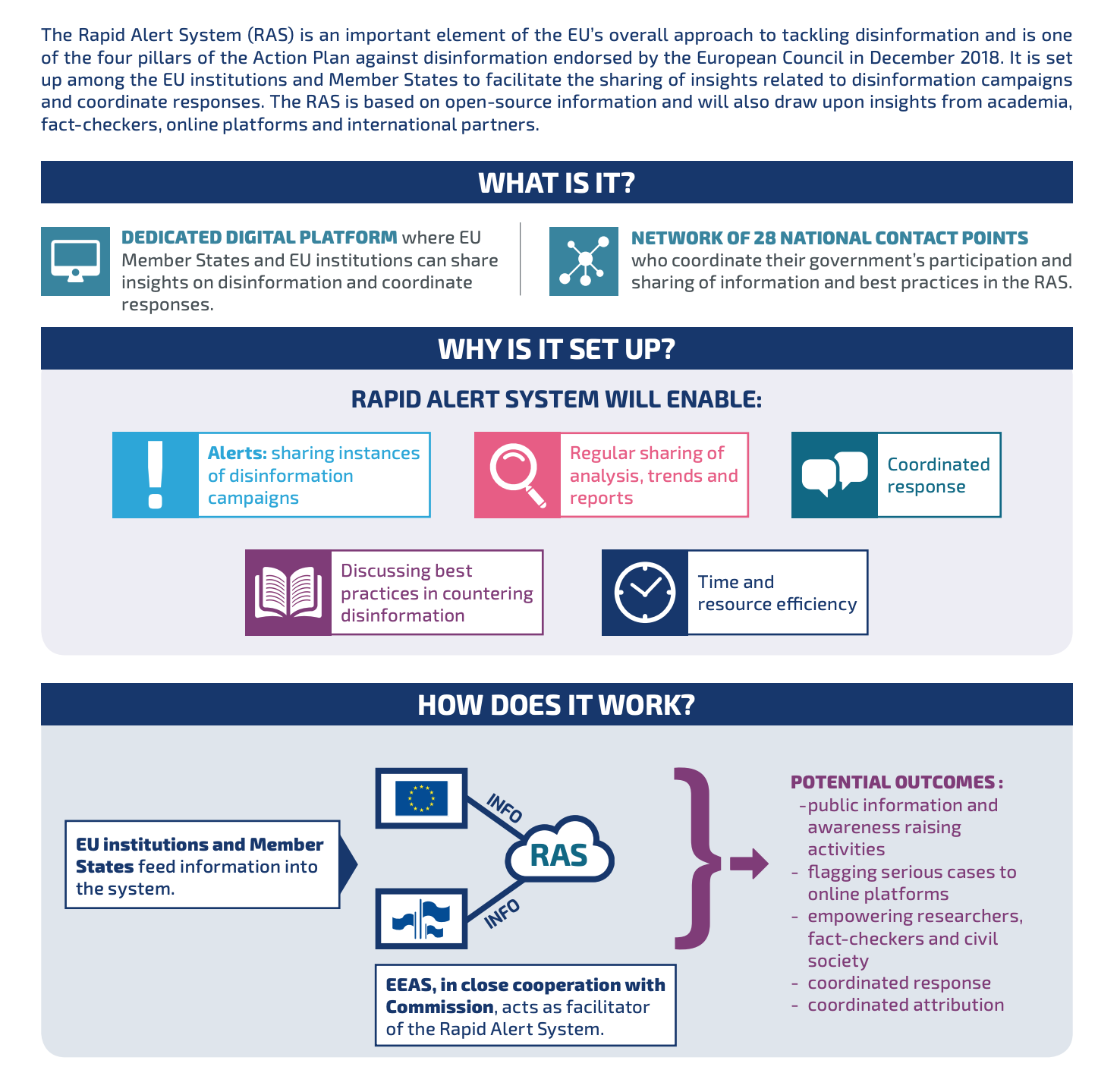

The New York Times has a front page article critiquing the EU's new Rapid Alert System (RAS), which was established to identify disinformation related to elections and to issue a rapid alert, warning voters in the EU. Any EU member country can notify the EU office of possible election disinformation. The Rapid Alert System was set up as a part of the EU's Action Plan against disinformation, which followed on the heels of the East Stratcom Task Force, which is tasked with countering Russian disinformation. The NYT article reports that some in Brussels, where the EU's disinformation analysts are stationed, jokingly describe the Rapid Alert System as follows: "It's not rapid. There are no alerts. And there's no system." The NYT article includes one incident in which EU officials identified suspicious tweets about an "Austrian political scandal," which may have been from Russian trolls, but the EU officials--for whatever reason--did not issue an alert. In fact, the office never issued any alerts during the last election season, although officials claim that they were successful in protecting the EU elections from interference.

One expert the NYT quotes, Jakub Janda, the executive director of a Czech-policy group, described the Rapid Alert System as a failure: "It's a Potemkin village. People in the know, they don't take it seriously." Few countries have contributed to the RAS, although it is not clear the reason for the lack of submissions stems from members' low view of the RAS or simply the lack of problematic cases of election disinformation. EU officials defend the system as the first of its kind and the office is cautious about issuing an alert. Presumably, too many alerts would undermine its effectiveness.

Although the NYT article provides helpful information about the RAS, it seems too early to tell how well it operates after just one election. The fact that no alerts issued during the past election is not evidence, in itself, of a failure of the system. The EU officials' cautiousness in issuing alerts seems wise as their effectiveness would likely be diminished if alerts were frequently issued for every single piece of election disinformation. In some cases, an alert might give more viewers to a piece of disinformation, also known as the Streisand effect. More generally, the experience shows the complex set of issues regulators face in trying to ensure the integrity of elections. The EU does not take the same broad approach to free speech as the U.S. does, so the EU regulators have more authority to combat disinformation. Yet, even with more expansive power, it's not clear how EU regulators can best fight election disinformation online, where posts and ads can have an effect on people as soon as they are viewed.